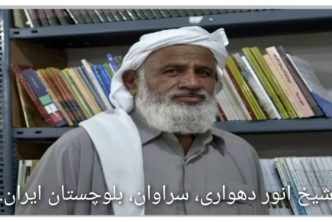

Emadeddin Baghi had been imprisoned once for 3 years in 1379- 1381 (2000-2002) due to his articles about “criticizing the death penalty” and “clarifying and enlightening about the murder of Persian intellectuals”. After being released, he had been focused on Human Rights Literature together with research and writing and thus established the association for the defense of prisoners’ rights. Also he created another association devoted to criticizing the death penalty. He practically involved in prisoners’-related issues.

He was imprisoned again in 22 Mehr 1386 (14, October 2007) thanks to writing a collection of articles in Persian Medias inside the country and he will return to prison next week at the conclusion of a temporary leave for medical treatment . In the last days of his temporary leave, he was informed that he has appointed and nominated by the Foreign Press Association and the judges of the British Press Awards as the International Journalist of the Year 2008. Today (8^th of April) the ceremony will be held in London. Since Baghi has been banned to leave the country, Mr. Drewery Dyke (one of the authorities of Amnesty International) will take part on his behalf and will read his article and receive the prize.

this is his article:

Emadeddin Baghi, Tehran, Iran

Statement for the British Press Awards

From a great distance and with a heart close to you, I greet all the journalists who defend freedom of expression in the world. I thank the Foreign Press Association for nominating me and the judges of the British Press Awards for honouring me with the award of International Journalist of the Year 2008.

The print media has always been the platform of raising awareness, integrity, moral standards and scientific progress in the world; it has advanced Montesquieu’s notion of “separation of powers” and has, in its position as the Fourth Estate, complemented it.

Tonight, friends, I am addressing you from a land that still tastes the bitterness of bans on the press in spite of having a history of 150 years of striving for democracy. In the past 10 years, about 150 publications have been banned, although none of them were hostile to the Islamic Republic. They were only independent and reform-minded.

I am addressing you from a land with an ancient civilisation, yet where some people have changed Darwin’s theory of survival of the fittest to that of ‘death of the fittest’. Many newspapers have been sent into darkness as soon as they have neared their professional maturity and wielded influence; as if a newspaper’s chances of survival grew dimmer the higher its print run, the more its number of readers and the stronger it became.

I am addressing you from a land, where newspapers are not seen as civil but rather as political institutions. Instead of the intelligentsia, press associations and people, it those that wield power – the rulers – who decide the fate of the press.

They fear freedom of the press. Here in Persia the power wielders have freedom of expression and the scope to slander, libel, threaten and imprison the dissidents.

There have been many instances where citizens have been prosecuted for having exercised their right to freedom of expression, despite having complied with the law of the land and human rights principles

Tonight, friends, I am addressing you from a land where I have personally been eye-witness to the tearful eyes of journalists, whose emotions and livelihood were plunged into crisis when their newspapers were banned. They whispered the question:

Would a factory or an organisation be shut down or a large number of people and an organisation destroyed if an individual allegedly committed an offence?

Yet, many newspapers were banned and their journalists detained before their guilt was established by any a fair judicial process.

I wrote back in 1999 that the closure of each newspaper is tantamount to murder and we that should organise a movement for the “collective commemoration” of banned newspapers and hold memorials on the anniversary of their ‘deaths’; we should build memorials for them to shine a light on the ugliness of the war on the press .

Today, I say we, journalists of the world, should create a monument – similar to monuments in many countries for the fallen of the patriotic and liberation wars where their names are inscribed – for these banned newspapers and all the victims of journalism all over the world, in order to prevent history from forgetting; to prevent the forgetting of history.

As a scholar and writer, who has simultaneously worked as journalist, occasionally as editor or advisor in the press for the past quarter of a century, who has been imprisoned for the second time for an anthology of articles in lawfully published newspapers of the country, and will return to prison next week at the conclusion of a temporary leave from prison for medical treatment.

I console myself with the thought that it is not only Persian journalists and writers but also journalists and heralds of freedom of expression in the UK and throughout the world who endeavour to prevent the forgetting of newspapers fallen on the path of knowledge and free flow of information.

I bring my address to a conclusion by citing the first and last stanzas from a poem of the great Persian intellectual and journalist, Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, which he wrote one hundred years ago to mourn Sur-Esrafil, the first martyr of Persian newspapers, who was hanged at the hand of tyranny:

O’ bird of dawn!

When the dark night,

Has finally ended its darkness,

Remember the dead candle, remember!

Expressing my gratitude to British Press Awards and wishing for a world of peace, tolerance and freedom of expression! To freedom, my friends!

Emaddedin Baqi