THE BOSTON GLOBE -Friday, 01-Sep-2006 17:03:58 ED

By Anne Barnard, Globe Staff | August 30, 2006

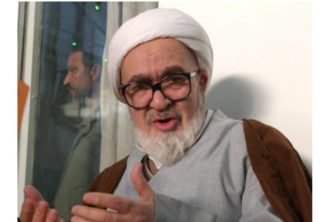

TEHRAN — Emad Baghi is a human rights activist who spent three years in prison for his writings. Shadi Vatanparast is a promoter of underground Iranian rock bands who, in the semi-privacy of her office, throws off her government-mandated headscarf. And Fazel Mehbadi is a mullah who preaches a message that’s dangerously dissident in the theocratic Islamic Republic of Iran: Religion should be separate from government.

These Iranians, in large ways and small, want more democracy and pluralism in their country, and they have taken risks to change their society. They are the kind of people whom US officials say they want to support. Yet they all agree that the last thing they need is help from the United States .

“The best thing the Americans can do for democracy in Iran is not to support it,” Baghi, the activist, said recently in his office, next to a stack of his politically risky published books — “The Tragedy of Democracy in Iran,” “Clerics and Power,” and a study that criticizes the government on its own terms, using Islamic teachings to indict Iran’s justice system and its arbitrary arrests and executions.

Receiving US aid — whether cash or simply public statements of support — could destroy democracy advocates’ chances of building grass-roots credibility at home, say Baghi and many other Iranians critical of their government. They prefer to steer their own course, pushing for gradual change and navigating a middle ground between accommodation and conflict with the Muslim clerics who rule Iran .

Their goals vary, though none would sound out of place on an American wish list: Baghi pushes for the rule of law; Mehbadi, the cleric, wants more power for elected officials; and Vatanparast, the music promoter, wants to midwife young Iranians’ yearning for social and cultural freedom, a force that has already pushed the government to accept, tacitly, a looser dress code for women.

But they all agree that the chaos and violence that have come with US-imported democracy in neighboring Iraq and a US Middle East policy that Iranians view as uncritically supportive of Israel — especially during the war in Lebanon — have darkened Iranians’ view of the United States. Against the backdrop of decades of mistrust and misunderstanding between the two countries, the new tensions have made Iranians more skeptical that American-style democracy would improve their lives.

It is a view echoed by democracy activists across the Middle East , from Cairo to Damascus . But it is particularly striking in Iran , a country with a sophisticated population and a huge diaspora in the United States that would seem to be fertile ground for American efforts to spur skepticism of the government, the way the Voice of America once did in the Soviet Union .

The Bush administration plans to spend $85 million by the end of 2007 to promote democracy in Iran — far more than the current $10 million program. The new plan includes $50 million to expand Farsi-language satellite broadcasts and make them strong enough to overpower Iranian jamming. The rest would support civic organizations and political and human rights activists inside and outside Iran .

The Iranian government lodged a formal diplomatic complaint denouncing the plan as US interference, and official rhetoric links American “liberal democracy” to the deaths of fellow Muslims in Iraq and Lebanon .

More noteworthy is the backlash against the plan — and against the United States more broadly — among ordinary Iranians, who even if they dislike US policy generally, still like Americans and much of US culture, whether they are drawn to US education and technology or American fashion and music.

Decades of mistrust

Vatanparast, 26, the music promoter, wears jeans and running shoes under her required thigh-length jacket and headscarf, is well versed in American music from jazz to rap, and even has a CD of klezmer music on her desk, a minor rebellion under a government that often demonizes Jews. But she no longer sees the United States as a model.

“Whatever America is selling, I’m not buying,” she said one recent morning, in the downtown Tehran office where she and other young Iranians run a virtual music festival. They promote bands that operate outside the government-approved music industry, by posting their tracks on a website where fans vote for their favorites. The first festival in 2003 drew 21 bands; this year, there were 87.

“You can’t change a country by attacking it. You kill people to create change?” she said. “The price for this change is too high.”

Iranian anger at the US government dates back to a Cold War power play in 1953, when the CIA helped engineer the overthrow of Iran ‘s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, to shore up the power of the Shah. Iranians overthrew the Shah’s monarchy in 1979, led by clerics who launched the modern world’s first Islamic government and held Americans hostage in the US Embassy for 444 days. Diplomatic relations with Washington have never been restored.

Thousands of Tehran residents lit candles in a public square to show sympathy for Americans after the Sept. 11 attacks. But since then, mistrust has grown. President Bush has labeled Iran part of an “axis of evil,” and Iranians fear a US military attack.

Tensions have risen over the country’s alleged nuclear weapons program and sponsorship of the Lebanese militia Hezbollah. And Iranians have watched US invasions of neighboring Afghanistan and Iraq , which promised freedom and democracy, usher in years of violence on their eastern and western borders.

In a country that boasts 2,500 years of Persian history and identity, and a political system with far more internal give and take than Saddam Hussein’s Iraq , finding a homegrown solution is a point of pride, Vatanparast explained.

In some ways, that approach is working. Over the years, the carapace of government restrictions imposed in the name of Islamic purity has loosened, under popular pressure that Vatanparast compares to a chick bursting from an eggshell: “People are pushing from inside. [The shell] is getting thinner and thinner.”

Police often turn a blind eye now to private drinking, despite a ban on alcohol, and are less likely to stop couples from socializing in parks and restaurants.

Vatanparast remembers not even being allowed to wear colored socks to elementary school, while now many women shun long coats or all-enveloping black chadors, once mandatory, for shorter jackets and colorful scarves that daringly expose much of their hair.

At the same time, many Iranians say tolerance of new social freedoms is partly a government strategy to cool discontent while cracking down on political dissent.

A limited dissent

Iran ‘s parliament and president are elected with a measure of real competition — voters sometimes deliver surprise victories — but ultimate power rests with an unelected body of clerics that appoints the all-powerful supreme leader and approves candidates for elected office, routinely disqualifying most would-be contestants.

The state still holds political prisoners, like Ramin Jahanbegloo, a prominent philosopher arrested in April on vague charges of associating with foreigners. Another prisoner, Akbar Mohammedi, arrested after leading student protests in 1999, died during a hunger strike last month. And this month the government outlawed Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi’s Center for Defending Human Rights, a group that has exposed regime abuses.

Vatanparast has no illusions, and she urges musicians to set pragmatic limits.

“There is no democracy or freedom of speech, so we advise them to use apolitical themes,” she said.

But she also knows how to push the envelope. If a song praises Ali, the most revered figure in the state religion of Shi’ite Islam, it can have an edgy rock beat, she said.

Or a traditional Iranian song can become widely understood as an _expression of dissent — like “Morgh e Sahar,” or “Bird of Daybreak,” a song that laments “the cruelty of tyrants” and calls on a nightingale to break out of its cage and “compose the song of freedom for humankind.”

Vatanparast’s office is a sanctuary from the rules imposed in other workplaces; women chat with male colleagues without wearing their headscarves. But for all her cultural openness, she doesn’t like what she sees of America , via CNN and Oprah: consumerism, obsession with celebrities, and political apathy.

Perhaps there is no better evidence of Iranians’ openness to alternate viewpoints than the bustling business in satellite dishes, which defies a government ban on owning or installing them.

So many households have them that the government, winking at its own ban, has even launched its own satellite programs — mostly soap operas and other entertainment — to compete with the ones beamed in from Europe , Turkey , and America , including Farsi channels based in Los Angeles , where many expatriate Iranians live.

A 41-year-old man who installs 20 dishes a week said American programs are among the most popular. He favors “Animal Planet.”

But the technician, who asked not to be named because he could be jailed or fined for his work, said new programming will not win America friends because American news channels display the fallout from US policies that nearly all Iranians find troubling: chaos in Iraq, Israeli bombings in Lebanon, and Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories.

While much of the country limits its rebellion to clothing, movies, and music, some religious scholars have tried to reform the political system from within, calling for elected officials to have more clout.

But the reformist movement — led by former president Mohammed Khatami, who allowed new social and intellectual openness — faltered last year when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a populist and foreign-policy hard-liner, won the presidency in an electoral upset. Dejected reformists now say Khatami’s emphasis on increased intellectual freedom failed to win over the masses who wanted economic improvements.

So Fazel Mehbadi, 53, takes a different tack, insisting on a reform of religion itself, which, he said, matters more to the average person than politics.

Mehbadi, a cleric and researcher at Mofid University in the holy city of Qom , isn’t allowed to teach students or lead a mosque because he openly argues that state power corrupts religion and that clerics shouldn’t be rulers.

Mehbadi abhors laws forcing women to cover their hair and wants Iranians to have more say over their leadership.

But he, too, says direct US help would be harmful to his cause. “Every nation must learn for itself how to be democratic,” he said. “No nation will accept democracy if there is a foreign cultural force behind it.”

www.boston.com/news/world/middleeast/articles/2006/08/30/iranians_taste_freedoms_on_own_terms