September 25, 2006 New York Times

Iranian Clerics’ Angling Stirs Worry on Absolute Rule

By NAZILA FATHI

TEHRAN, Sept. 24 — Political jockeying by fundamentalist Iranian clerics for the coming election of the Assembly of Experts, the group charged with overseeing the country’s supreme leader, is raising concerns that the government will move further toward authoritarianism.

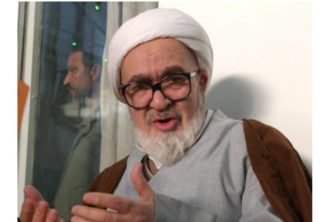

As in the last elections for the assembly eight years ago, the watchdog Guardian Council has barred reformist clerics. And this year, some clerics and some newspapers have been suggesting that a senior fundamentalist cleric who is President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s mentor, Muhammad Taqi Mesbah Yazdi, may be trying to expand his already growing power by packing the assembly with loyalists trained at his education center in Qum .

Mr. Mesbah Yazdi, 72, is close to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and he directly influences the government through loyalists appointed to high posts after Mr. Ahmadinejad took power last year. His followers also have great sway among Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and the Basij volunteer paramilitary force.

The Iranian Constitution adopted after the 1979 revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini provided for a system of checks and balances meant to ensure that the government would not move toward authoritarianism. So even as it enshrined a supreme leader, who has the final word on all matters, it created an Assembly of Experts, or religious jurisprudence, to oversee his activities.

But after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, a system of vetting election candidates was put in place to eliminate any threat to the rule of the supreme leader.

At least on paper, the official powers of the Assembly of Experts include the ability to replace the supreme leader if he acts against Islam or the Constitution.

However, Mr. Mesbah Yazdi and Ayatollah Khamenei are allies — the ayatollah finances Mr. Mesbah Yazdi’s school in Qum — and the likeliest outcome of a power play by Mr. Mesbah Yazdi would be to strengthen the supreme leader, even at the expense of the Assembly of Experts.

Mohsen Kadivar, a senior reformist cleric who was barred from running in the last election, said, “The fight in the election will be between the traditional clerics and the fundamentalists.” He identified the traditionalists as those who considered the Assembly of Experts a higher authority than the supreme leader.

Mr. Mesbah Yazdi is a particularly aggressive defender of the supreme leader’s absolute power, and he was a strong critic of the previous president, Mohammad Khatami, who tried to introduce modest social and political changes. He has long held that democracy and elections are not compatible with Islam.

“Democracy means if the people want something that is against God’s will, then they should forget about God and religion,” he said in July 1998. “Be careful not to be deceived. Accepting Islam is not compatible with democracy.”

And in November 2002, the daily Aftab-e-Yazd quoted him as saying: “Who are the majority of people who vote: a bunch of hooligans who drink vodka and are paid to vote. Whatever they say cannot become the law of the country and Islam.”

He has criticized democracy more cautiously since the election of Mr. Ahmadinejad, but his disdain for the election process to fill the Assembly of Experts was evident in a speech in Mashhad this month, in which the news agency ISNA quoted him as saying it was like the vote of the “ignorant for the learned.”

Mr. Mesbah Yazdi was a founder of the modern Haghani School , a religious school in Qum where most Iranian officials were trained.

After Ayatollah Khomeini died, Mr. Mesbah Yazdi founded the Imam Khomeini Education and Research Institute. Since then, he has grown close to Ayatollah Khamenei.

Through the school, he has educated more than 700 students who are extremely loyal to him, according to people who work in Qum , but, out of fear of retribution, would speak only on the condition of anonymity. Many of his followers are believed to be running for the Assembly of Experts.

These protégés are clerics but have studied the humanities, and many have received degrees from Western universities like McGill in Montreal and Manchester in London .

The elections for the Assembly of Experts, the fourth since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, is scheduled for Dec. 15. Many of Mr. Mesbah Yazdi’s young and seemingly modern clerics are believed to be running, but as independent candidates to avoid announcing their affiliation to Mr. Mesbah Yazdi. However, it is difficult to be sure exactly how many, or which, candidates are allied with him because of the secrecy that often blankets elective matters here.

Some analysts say the competition this year is likely to be between Mr. Mesbah Yazdi and Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a former president who packed the assembly elected in 1990 and 1998 with traditional clerics with whom he had influence.

But Mr. Rafsanjani, who represents more moderate and pragmatist views, has not announced his candidacy, and some political analysts say he may not run if the prospect of winning the prestigious position of the leader of the assembly seems dim. He lost to Mr. Ahmadinejad in last year’s presidential elections and suffered a defeat in parliamentary elections six years ago. His son, Mehdi Hashemi, said Mr. Rafsanjani had “set a condition and his participation depends on that.” But he declined to specify the condition.

Turnout was a low 37 percent in the second assembly election, in 1990, in part because voters felt little connection to it.

“People have not received any reports about the activities of the Assembly of Experts, and no one can even imagine the supreme leader can be replaced,” said Mohammad Atrianfar, a close aide to Mr. Rafsanjani and the publisher of the daily newspaper Shargh, which was shut down this month. “People have no positive or negative reaction toward the assembly.”

In 1998, 46 percent voted after the landslide presidential victory in 1997 of Mr. Khatami, who urged people to vote in the assembly elections.

This year, to bolster turnout, the election authorities decided to hold the assembly vote at the same time as local elections. But requiring the candidates to be approved by the Guardian Council, some analysts say, undermines the point of the vote.

“If the members are independent and genuinely carry out their duty, the Islamic Republic can become democratic,” said Emadedin Baghi, a reformist journalist who studied religion for many years. “But vetting its candidates has put a cancerous tumor in the assembly which does not allow it to function properly.”